Le futur numéro un chinois a d’abord connu la vie privilégiée des enfants de la dynastie rouge. Puis, après la disgrâce de son père, ancien compagnon de Mao, la misère, l’enfer de la rééducation et du travail forcé. Itinéraire d’un homme qui n’a rien oublié…

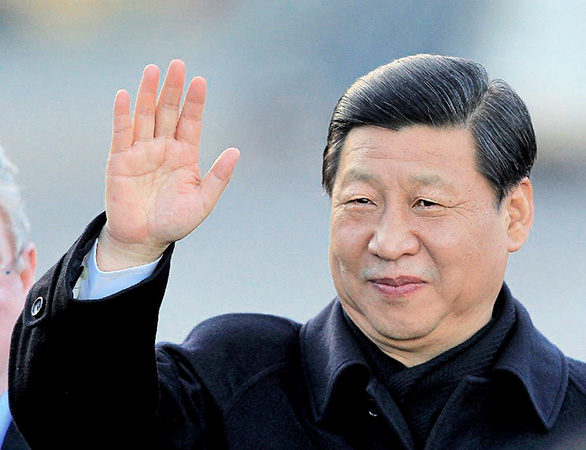

À un mois du 18e congrès du Parti qui doit installer, à partir du 8 novembre, une nouvelle équipe dirigeante à la tête du pays, on ne connaît toujours pas le nombre exact de sièges à pourvoir ni le nom des candidats et encore moins leur programme… Le pouvoir chinois reste un univers cadenassé où tout est secret d’État. En 2002, au moment où Hu Jintao accédait aux fonctions suprêmes, on savait si peu de choses sur lui que la blague la plus répandue était : «Who’s Hu?» Dix ans plus tard, on n’est pas beaucoup plus avancé, Hu ne s’étant jamais départi de son masque de technocrate dénué d’émotions. À l’heure où il s’apprête à passer le relais, son successeur désigné, Xi Jinping, suscite les mêmes interrogations. Quelles sont ses convictions ? ses projets ? ses priorités ? Quelle politique va-t-il mener ? Va-t-il se contenter de gérer l’acquis, de « maintenir la stabilité » coûte que coûte comme son prédécesseur ? Où va-t-il enfin lancer les réformes politiques nécessaires pour répondre efficacement aux graves problèmes sociaux et établir un système plus juste ?

Xi Jinping se garde bien de donner des réponses précises. Comme Hu en son temps, il s’interdit toute opinion trop tranchée qui pourrait inquiéter l’une des factions, heurter un baron rival ou déplaire à l’un de ses propres protecteurs. Profondément traumatisée par les déchirements et les délires de l’époque maoïste, la dynastie rouge craint comme la peste les personnalités fortes. Le numéro un doit donc être un homme de compromis, de consensus, qui devra naviguer parmi les infinies subtilités d’un système de clans et de coteries. D’où l’étiquette d’apparatchik insipide que certains s’empressent de coller au successeur désigné. Une sorte de Hu bis dont il n’y a rien de sérieux à espérer.

Xi Jinping se garde bien de donner des réponses précises. Comme Hu en son temps, il s’interdit toute opinion trop tranchée qui pourrait inquiéter l’une des factions, heurter un baron rival ou déplaire à l’un de ses propres protecteurs. Profondément traumatisée par les déchirements et les délires de l’époque maoïste, la dynastie rouge craint comme la peste les personnalités fortes. Le numéro un doit donc être un homme de compromis, de consensus, qui devra naviguer parmi les infinies subtilités d’un système de clans et de coteries. D’où l’étiquette d’apparatchik insipide que certains s’empressent de coller au successeur désigné. Une sorte de Hu bis dont il n’y a rien de sérieux à espérer.

Pourtant tout oppose les deux hommes. Grâce aux nombreuses informations dévoilées par WikiLeaks et au flot de publications à Hongkong et à Taïwan, c’est l’image d’une personnalité particulièrement forte et réfléchie qui émerge, héritière d’une histoire dramatique. Sur le plan du style d’abord. Malgré sa prudence et sa discrétion, Xi Jinping exhibe l’assurance innée des rejetons des dignitaires qu’on appelle ici les « princes rouges ». Quand il naît en 1953, son père, Xi Zhongxun, est vice-Premier ministre. Le petit Jinping connaît une enfance ultra-privilégiée dans le cadre idyllique de Zhongnanhai, vaste ensemble de parcs, de lacs et de palais aux toits dorés situé à deux pas de la place Tiananmen, dans une annexe de la Cité interdite où vit et travaille la poignée de hauts dirigeants. Alors que les Chinois sont plongés dans la misère, ces familles mènent grand train, avec cuisiniers, gouvernantes et chauffeurs. Comme tous ses camarades, le petit Xi fréquente une école d’élite où on lui inculque la conviction qu’il est un héritier de la révolution.

Xi Jinping, comme les autres leaders chinois, plante un jeune arbre, à Pékin, le 3 avril 2012, lors d’une campagne de reboisement volontaire, lancée par le président Hu Jintao.

Mais, en 1962, l’ire de Mao s’abat sur Xi Zhongxun, accusé d’activité antiParti et jeté en prison pour dixsept ans. Xi Jinping a alors 9 ans. C’est la cassure. La famille est expulsée du paradis, les enfants livrés à eux-mêmes. En 1966, quand éclate la Révolution culturelle, il est encore trop jeune pour faire partie de ces terrifiants « gardes rouges » qui martyrisent leurs aînés au nom de Mao. D’ailleurs, il n’est qu’un fils de « contre-révolutionnaire » et doit dénoncer quotidiennement son père, ce dont il gardera un souvenir horrifié. À 14 ans, il est envoyé à la campagne, dans une région misérable du Shaanxi où le vieux Xi avait jadis dirigé une guérilla. Pendant sept ans, il va y mener la dure vie des paysans, mangeant du gruau, gardant les moutons, transportant de lourdes charges à la palanche et dormant dans une habitation troglodytique sans eau ni électricité.

Il souffre de solitude, loin des siens. Mais il est costaud, il travaille dur. Il apprend à produire du biogaz avec le lisier de cochons, remporte des tournois de lutte et s’attire la sympathie des paysans. Encore adolescent, alors que son père croupit toujours en prison, il décide de survivre « en devenant plus rouge que rouge ». Il veut vaincre la disgrâce et conquérir sa place au sein du Parti. Il y sera finalement admis en 1974, au bout de la neuvième demande. Le village le bombarde immédiatement secrétaire de la branche locale du PC, il a 21 ans. Un an plus tard, sa vie bascule à nouveau : à la demande des villageois, il est admis à la prestigieuse université Tsinghua à Pékin, d’où il sortira avec un diplôme d’ingénieur chimiste.

La Chine vit alors un tournant historique. En 1978, Deng Xiaoping prend le pouvoir et tourne la page maoïste. Réhabilité, Xi Zhongxun est nommé à la tête de la province du Guangdong où il est le premier à expérimenter les fameuses réformes économiques qui feront de la Chine, trente ans plus tard, la deuxième puissance mondiale. C’est également lui qui crée dans un village de pêcheurs la première « zone économique spéciale », la fameuse cité de Shenzhen. Grâce à l’entregent paternel, Xi Jinping devient le secrétaire d’un général qui préside la puissante Commission militaire. Les portes de la reconquête lui sont ouvertes.

Les dépêches de WikiLeaks le décrivent comme un jeune homme ambitieux, décidé à se forger une carrière à la force du poignet. Alors que ses amis « princes », qui ont tous souffert de l’exil rural, s’enivrent de fêtes, d’alcool et d’idées venues d’Occident, Xi étudie le marxisme et s’abstient de courir les filles qui le trouvent d’ailleurs « ennuyeux ». Bon nombre de « princes » se détournent de la politique, préférant une carrière dans les arts, le business ou à l’étranger. Pas Xi Jinping, qui décide au contraire, en 1982, d’aller travailler comme secrétaire local du PC dans une sous-préfecture, loin du confort de Pékin et de la protection de son père.

Ses amis ne comprennent pas son choix. Il répond que les années passées auprès des paysans du Shaanxi lui ont donné le goût de l’action politique et la conviction qu’il est « bon à ça ». Grâce à son père, il possède un réseau au sein de l’élite politique et une connaissance intime du fonctionnement du système. Il lui doit surtout la conviction que des dirigeants communistes dévoués sont indispensables pour une Chine forte et une société juste. Pendant les vingtcinq années suivantes, Xi Jinping gravit les échelons un à un. Partout où il passe, il laisse le souvenir d’un responsable « pragmatique, prudent, bosseur et modeste ». Il devient patron de province – le Fujian, le Zhejiang, puis Shanghai – sans changer de style. Sous son règne, des ONG, des syndicats non officiels fleurissent, des candidats indépendants sont élus aux assemblées locales. Xi favorise les échanges commerciaux avec Taïwan et le développement des PME. Au fil du temps, il acquiert une véritable expertise en business. Mais c’est la théorie marxiste qu’il choisit d’étudier par correspondance, obtenant un doctorat en 2002, à l’heure où ses collègues se tournent vers les études de management. Xi veut posséder les titres de ses ambitions et dissiper à l’avance la méfiance que son statut de « prince » ne manquera pas de susciter.

Ses amis ne comprennent pas son choix. Il répond que les années passées auprès des paysans du Shaanxi lui ont donné le goût de l’action politique et la conviction qu’il est « bon à ça ». Grâce à son père, il possède un réseau au sein de l’élite politique et une connaissance intime du fonctionnement du système. Il lui doit surtout la conviction que des dirigeants communistes dévoués sont indispensables pour une Chine forte et une société juste. Pendant les vingtcinq années suivantes, Xi Jinping gravit les échelons un à un. Partout où il passe, il laisse le souvenir d’un responsable « pragmatique, prudent, bosseur et modeste ». Il devient patron de province – le Fujian, le Zhejiang, puis Shanghai – sans changer de style. Sous son règne, des ONG, des syndicats non officiels fleurissent, des candidats indépendants sont élus aux assemblées locales. Xi favorise les échanges commerciaux avec Taïwan et le développement des PME. Au fil du temps, il acquiert une véritable expertise en business. Mais c’est la théorie marxiste qu’il choisit d’étudier par correspondance, obtenant un doctorat en 2002, à l’heure où ses collègues se tournent vers les études de management. Xi veut posséder les titres de ses ambitions et dissiper à l’avance la méfiance que son statut de « prince » ne manquera pas de susciter.

À plusieurs reprises au cours de sa carrière, Xi Jinping est amené à « nettoyer » les dégâts de gros scandales de corruption, récoltant le surnom de « Monsieur Propre ». Lui-même mène une vie frugale, prend ses repas à la cantine, circule en minibus et refuse la classique voiture avec chauffeur. Il décline les cadeaux, pots-de-vin et autres avantages. Insensible aux honneurs et au décorum, il déteste que l’on fasse état de sa haute extraction. Les dépêches de WikiLeaks le décrivent comme « non corrompu, pas intéressé par l’argent », et même « révolté par la commercialisation généralisée de la société chinoise, avec ses nouveaux riches, ses fonctionnaires corrompus, sa perte des valeurs, de la dignité et du respect de soi ».

Émeute ouvrière sur le site de l’usine Foxconn de Taiyuan (dans la province de Shanxi), le 24 septembre

Xi Jinping n’hésite pourtant pas à se ranger sous l’aile de l’ancien président Jiang Zemin, malgré les casseroles qui entachent notoirement sa réputation. En effet, sans « protecteur », pas de carrière politique en Chine. Or Jiang, qui est le puissant chef de file des « princes » et le patron du clan des Shanghaïens, a les moyens de pousser son poulain lors des consultations internes qui déterminent les promotions. C’est ce qu’il fera pour favoriser l’ascension de Xi, jusqu’à obtenir en 2002 sa désignation comme candidat à la succession. En retour, Xi devra « prendre soin » de Jiang et de son réseau, protégeant le vieux leader contre toute tentative d’exhumer les nombreux cadavres qui remplissent ses placards…

Xi Jinping se plie aux règles du jeu. Il endosse l’étiquette de « prince » mais sans l’arrogance, ni l’esprit de caste et encore moins le goût du bling-bling. Il sera le plus « peuple » des princes, ce qui lui vaudra également la sympathie du clan opposé, la Ligue, et de son chef, le président Hu Jintao. Ce dernier a pourtant un autre candidat à sa propre succession, Li Keqiang, issu comme lui de la Ligue. Mais les votes informels organisés lors de diverses rencontres sont clairs : l’aimable Xi remporte plus de 90 % des suffrages ! Les deux clans tombent d’accord sur le « candidat du compromis ». Trente-cinq ans après s’être promis de reconquérir le Parti, Xi Jinping est désigné comme dauphin (et vice-président) en 2007.

Le prochain numéro un a un atout cœur : son épouse, bien plus célèbre et depuis bien plus longtemps que lui, la chanteuse Peng Liyuan, membre d’une troupe de l’armée – ce qui lui a permis, accessoirement, de cultiver les liens avec les militaires. Pour les nombreux Chinois qui attendent impatiemment des réformes politiques, c’est la figure du père Xi qui autorise tous les espoirs. Xi Zhongxun a en effet osé s’élever à trois reprises contre l’autorité du leader suprême et a payé à chaque fois son courage par la disgrâce. « Non seulement Xi Jinping connaît exactement la situation des plus déshérités, ayant lui-même enduré de grandes souffrances pendant la Révolution culturelle, mais il est le fils d’un héros dont le dernier acte politique a été de condamner publiquement les tueries de Tiananmen en 1989… Comment ne pas espérer qu’il ait hérité de lui quelques gènes ? », réagit un professeur pékinois qui a fréquenté le futur président. Pourtant, il est inquiet : Xi est un homme « trop bon, trop doux », explique-t-il. Comment pourra-t-il réformer un système totalement gangrené par des coalitions d’intérêts devenues gigantesques ? La décennie de Xi Jinping sera celle du combat contre l’hydre ploutocratique.

La mer de tous les dangers

Est-ce un effet des sourdes luttes entre clans à l’approche du 18e congrès ? Depuis le printemps, le torchon flambe entre la Chine et ses voisins riverains des mers de Chine orientale et méridionale – Vietnam, Philippines, Malaisie, Taïwan, Japon. Pékin revendique la totalité des îles et 80 % des eaux. Récemment, c’est autour de la question d’îlots inhabités – appelés Senkaku en japonais et Diaoyu en chinois –, actuellement administrés par Tokyo, qu’ont éclaté les manifestations nationalistes les plus violentes. La crise risque de dégénérer, de nombreux navires chinois essayant de pénétrer dans les eaux territoriales japonaises. Dans le même temps, le conflit autour des archipels Paracel et Spratly, en mer de Chine méridionale, continue de s’envenimer. Cette escalade générale de la tension laisse craindre que Pékin – ou plutôt la frange la plus nationaliste – ne se laisse aller à l’ivresse « classique » des pays qui accèdent brusquement au rang de puissance dominante et choisissent de s’imposer à leurs voisins par la force. Pourtant la Chine doit son émergence à son intégration au marché mondial et aux milliards apportés par le commerce et les investissements extérieurs. La détérioration du climat politique ne peut que nuire à une économie encore très peu autonome. Selon les observateurs, Xi Jinping est bien placé pour désamorcer cette crise. Ayant subi dans sa jeunesse les méfaits de la Révolution culturelle, il a en horreur les déchaînements de passions plus ou moins orchestrés. Grâce à son expérience à la tête de provinces accueillant des investissements étrangers, il n’en ignore ni la valeur ni la fragilité. Et surtout ses relations étroites avec les militaires le rendent apte à se faire écouter des troupes. Reste à savoir si la frange des « néo-maos », furieux du limogeage de leur champion, le « prince » Bo Xilai, ne cherchera pas à déstabiliser le nouveau pouvoir.

Est-ce un effet des sourdes luttes entre clans à l’approche du 18e congrès ? Depuis le printemps, le torchon flambe entre la Chine et ses voisins riverains des mers de Chine orientale et méridionale – Vietnam, Philippines, Malaisie, Taïwan, Japon. Pékin revendique la totalité des îles et 80 % des eaux. Récemment, c’est autour de la question d’îlots inhabités – appelés Senkaku en japonais et Diaoyu en chinois –, actuellement administrés par Tokyo, qu’ont éclaté les manifestations nationalistes les plus violentes. La crise risque de dégénérer, de nombreux navires chinois essayant de pénétrer dans les eaux territoriales japonaises. Dans le même temps, le conflit autour des archipels Paracel et Spratly, en mer de Chine méridionale, continue de s’envenimer. Cette escalade générale de la tension laisse craindre que Pékin – ou plutôt la frange la plus nationaliste – ne se laisse aller à l’ivresse « classique » des pays qui accèdent brusquement au rang de puissance dominante et choisissent de s’imposer à leurs voisins par la force. Pourtant la Chine doit son émergence à son intégration au marché mondial et aux milliards apportés par le commerce et les investissements extérieurs. La détérioration du climat politique ne peut que nuire à une économie encore très peu autonome. Selon les observateurs, Xi Jinping est bien placé pour désamorcer cette crise. Ayant subi dans sa jeunesse les méfaits de la Révolution culturelle, il a en horreur les déchaînements de passions plus ou moins orchestrés. Grâce à son expérience à la tête de provinces accueillant des investissements étrangers, il n’en ignore ni la valeur ni la fragilité. Et surtout ses relations étroites avec les militaires le rendent apte à se faire écouter des troupes. Reste à savoir si la frange des « néo-maos », furieux du limogeage de leur champion, le « prince » Bo Xilai, ne cherchera pas à déstabiliser le nouveau pouvoir.

Un espoir pour le Tibet ?

Intellectuels, journalistes, artistes et autres internautes ne sont pas les seuls à espérer de grandes choses du fils de Xi Zhongxun. Un groupe plus discret, celui des « princes pro-réformes » – idéologiquement opposés tant aux « princes néo-maos » qu’aux « princes du fric » –, attend également la relance de plus en plus urgente des réformes politiques mises en veilleuse depuis les événements de Tiananmen en 1989. Selon les bruits qui courent à Pékin, Xi aurait récemment rencontré leur chef de file, Hu Deping, pour discuter des réformes à entreprendre en priorité. Les deux hommes se connaissent bien, leurs pères, grands alliés politiques, ayant partagé la même disgrâce. Hu Deping est en effet le fils du fameux Hu Yaobang, qui fut premier secrétaire du Parti dans les années 1980, et il reste à ce jour le leader le plus réformateur et le plus populaire de Chine. Sa destitution en 1987, pour cause de « mollesse » vis-à-vis des manifestations étudiantes, entraînera également la purge de Xi Zhongxun, ce dernier ayant été le seul haut dirigeant à protester. En 1989, la mort de Hu Yaobang déclenche le printemps des étudiants qui sera noyé dans le sang. Les deux « anciens » Hu Yaobang et Xi Zhongxun avaient également un autre point commun : une position modérée sur la question tibétaine. Xi père ayant été le commissaire politique de l’armée qui avait envahi le Tibet, il avait tenté d’adoucir le choc pour les populations. Et quand Mao l’avait chargé de gérer les relations avec les grands lamas, il avait établi des liens d’amitié avec les jeunes dalaï-lama et panchen-lama. Xi Zhongxun avait réussi à conserver, à travers les tourmentes de la Révolution culturelle, la montre en or que lui avait alors offerte le dalaï-lama avant sa fuite vers l’Inde. Depuis la révélation de ces faits par WikiLeaks ainsi que d’autres détails – comme l’intérêt que Xi Jinping aurait porté au bouddhisme –, l’espoir d’une réouverture des négociations, bloquées depuis plusieurs années, renaît à Dharamsala. Un tel geste permettrait peut-être de stopper la vague dramatique d’immolations par le feu qui endeuille le plateau tibétain. Et, au-delà, de trouver une solution pacifique à cinquante ans de conflit.

Parution Le Nouvel Observateur 4 octobre 2012. — N° 2500

Traduction en anglais par Wordcrunch

THE MANY FACES OF XI JINPING – WILL CHINA’S NEW LEADER BRING REAL REFORM?

By Ursula Gauthier

NOUVEL OBSERVATEUR/Worldcrunch

His name is Xi Jinping (pronounced Shee Jin-ping). The future Chinese leader was born into privilege as a child of the « red dynasty. » His father was an old revolutionary companion of Mao’s. But after his father’s fall into disgrace, Xi experienced poverty, prison and the hardships of peasant life. What kind of leader will he be?

As the 18th Party Congress, which will install a new leadership team for the nation, starts, it is not known yet exactly how many delegates there will be, nor the name of the candidates — much less the details of their programs. The Chinese regime remains a hermetically sealed universe, run with a steady supply of state secrets. In 2002, when Hu Jintao came to power, so little was known about him that the most widespread joke was « Who is Hu? » Ten years later, things have not changed much. Hu never removed the mask of an expressionless technocrat.

Now that the time has come for him to step down, his designated successor, Xi Jinping, is arousing the same kind of speculation. What are his convictions? His projects? His priorities? What kind of policies will he promote? Will he be content just to manage the status quo, « maintaining stability » no matter what, like his predecessor? Or will he launch the political reforms that are needed if China’s grave social problems are to result in a more just system?

Xi Jinping has been careful not to give detailed answers. As Hu did before him, he has not let slip any hint of a firm opinion that might worry one of the factions, irritate a rival, or displease one of his own protectors.

The red dynasty, profoundly traumatized by the excesses and social cataclysms of the Maoist era, fears strong personalities like the plague. China’s leader must be a man of compromise and consensus, who can navigate an infinitely subtle system of clans and cliques. This is why many believe that Xi is nothing more than a bland apparatchik; a sort of Hu clone, from whom nothing serious can be expected.

Expelled from paradise

However, the two men are different in every way. Thanks to the torrent of information divulged by WikiLeaks, and to a flood of publications from Hong Kong and Taiwan, we can glimpse an especially strong, thoughtful personality whose life has seen dramatic ups and downs.

First there is the matter of his style. In spite of his prudence and discretion, Xi displays the innate assurance of the scions of top party leaders, whom the Chinese call « red princes. » When he was born, in 1953, his father Xi Zhongxun was vice-premier. Little Jinping had an ultra-privileged childhood in the idyllic Zhongnanhai, a vast enclosure of parks, lakes and golden-roofed palaces close to Tiananmen Square. Only the most elite of Chinese leaders worked and lived in this annex of the Forbidden City.

At a time when the rest of China was mired in deep poverty, these families lived a grand life, with cooks, nannies and chauffeurs. Like all the other children, young Xi went to an elite school where he was educated to believe that he was an heir to the revolution.

But in 1962, Mao’s wrath fell upon Xi Zhongxun, who was accused of anti-party activity and thrown into prison for 17 years. For nine-year-old Jinping, it was an abrupt break. His family was expelled from their paradise, the children left to their own devices. In 1966, when the Cultural Revolution broke out, he was too young to become one of the terrifying « red guards » who tortured their elders in the name of Mao.

He was just the son of a « counter-revolutionary,” and had to denounce his father daily. The memory still haunts him. At 14, he was sent to the countryside, to the miserably poor region of Shaanxi, where his father had once led a guerrilla war. For seven years, he lived the hard life of a Chinese peasant, eating gruel, herding sheep, gathering fodder, carrying heavy burdens with a shoulder pole, and sleeping in a cave dwelling without water or electricity.

Far from his family and friends, he suffered from loneliness. But Xi was young and tough and hard working. He learned how to produce biogas from pig manure, won wrestling matches, and made friends with the peasants. As a teenager, with his father still in prison, he had already decided to survive by becoming « redder than red. »

He wanted to overcome the disgrace and win his way back to the heart of the Chinese Communist Party. He was finally allowed to join in 1974, after his ninth request. The village immediately named him secretary of the local party branch. He was 21. One year later, his life changed again. At the villagers’ request, he was admitted to the prestigious Tsinghua University in Beijing. He graduated from Tsinghua with a chemical engineering degree.

Back in favor

China was then at a historical turning point. In 1978, Deng Xiaoping seized power and bade farewell to Maoism. Rehabilitated, Jinping’s father Xi Zhongxun was named governor of Guangdong province, where he was the first to experiment with the well-known economic reforms that, 30 years later, have turned China into the second economic power in the world. It was also Xi Zhongxun who chose a fishing village to be the first « special economic zone, » now the booming city of Shenzhen. Through his father’s connections, Xi Jinping became the private secretary of a general in charge of the powerful Military Committee. The doors to the Party were opening for him.

The WikiLeaks dispatches describe Jinping as an ambitious young man, determined to get ahead through sheer hard work. While his fellow « princelings » — who had all suffered exile to the countryside — were getting drunk, having parties, and turning to Western ideas, Xi was studying Marxism. He was not a lady’s man, and found most women « boring. » Many of the « princelings » chose other careers than politics, preferring the arts, business, or life abroad. Xi, on the contrary, decided in 1982 to work as a local party secretary in a sub-prefecture, far from the comfort of Beijing and his father’s protection.

His friends found his choice incomprehensible. He responded by saying that his years spent with the Shaanxi peasants had given him a taste for political action and the conviction that he was « good at it. » Thanks to his father, he had a network of political elite, and an intimate knowledge of how the system worked. To his father, too, he owed his conviction that devoted Communist leaders were indispensable for a strong China with a more just society. During the next 25 years, Xi climbed through the ranks, step by step. Everywhere, he left a reputation as a « pragmatic, prudent, hardworking, and modest » leader. He became a provincial governor, first of Fujian, then Zhejiang, then Shanghai, without changing his style.

Under his administration, NGOs and non-government-sponsored unions flourished, and independent candidates were elected to local assemblies. Xi Jinping favored commercial exchanges with Taiwan and the development of small business. Over time, he acquired a real expertise in business. But he continued to study Marxist theory by correspondence, obtaining his doctorate in 2002, at a time when his colleagues were turning to management studies. Xi wanted to deserve his promotion and dissolve in advance any mistrust that his position as « princeling » would naturally arouse.

Several times in his career, Xi has been called upon to « clean up » the damage from major corruption scandals, earning the nickname « Mr. Clean. » He lived a frugal life, took his meals in the cafeteria, and drove a minibus, not the usual chauffeur-driven car. He turned down gifts, bribes and other offers. He did not care about decorations and protocol, and hated it when people talk about his lineage. The WikiLeaks dispatches describe him as « not corrupt, not interested in money, » and even « revolted by the general commercialization of Chinese society, with its nouveaux riches, its loss of its values, dignity, and self-respect. »

Strategic alliances

In spite of the notorious stories that blackened Jiang Zemin’s reputation, Xi Jinping did not hesitate to line up with the former president. Without a « protector » there is no such thing as a political career in China. Jiang, the most powerful of the « princelings » and the boss of the Shanghai faction, had the means to promote his protégé in the internal consultations that determine who is promoted. Jiang pushed steadily for Xi, and in 2002 was able to get him designated as a leadership candidate. In return, Xi will have to « take care » of Jiang and his clique, protecting the old leader against any attempt to « dig up the bodies » that surround Jiang.

Xi Jinping played the game well. He bore the label of « princeling » without arrogance or snobbery, much less any taste for bling. He will be the most « man of the people » among the princes. This has brought him the support of the opposing group, the Communist Youth League, and its leader, Chinese head of state Hu Jintao. Hu, though, had his own candidate for his successor, Li Keqiang, also from the League. But the « informal votes » organized during various meetings were decisive: The likable Xi received more than 90 % of the vote. The two clans agreed on the « compromise candidate. » In 2007, thirty-five years after having vowed to re-conquer the Party, Xi Jinping was designated as heir apparent and vice-president.

The next leader has one unusual asset: his wife, army soprano Peng Liyuan, who is much more famous than he is, and has been for a long time. Her connection with the military has allowed Xi Jinping to make friends there, too.

For the many Chinese who are impatiently waiting for political reform, it is above all the figure of Xi Jinping’s father who allows them to hope. Three times, Xi Zhongxun spoke out against the authority of the supreme leader and was disgraced for his courage. « Not only does Xi Jinping know first-hand the situation of poverty-stricken people, having himself endured great suffering during the Cultural Revolution, but he is the son of a hero whose last political act was publicly condemning the Tiananmen killings in 1989…. How could we not hope that he has inherited some of his father’s genes? » says a Beijing professor who knows Xi Jinping well. However, he is concerned because Xi is « too good, too gentle.” How will he be able to reform a system totally corroded by now-gigantic coalitions of interest groups? The decade of Xi Jinping will be one of fighting the hydra-heads of plutocracy.

***

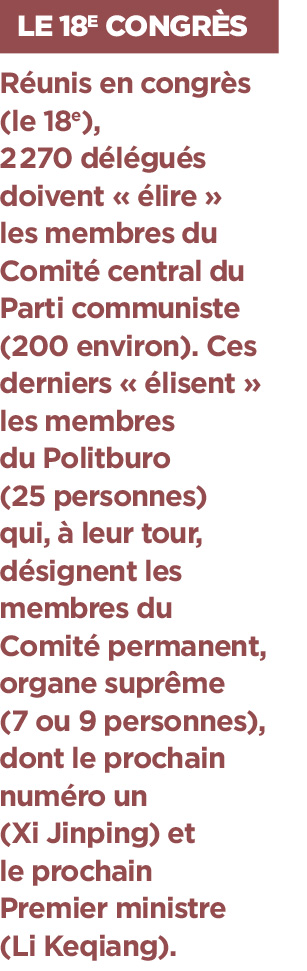

The 18th Party Congress

During the 18th Party Congress, 2,270 delegates will « elect » the members of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee — about 200 people. They in turn will « elect » the 25 members of the Politburo, who then designate the seven or nine members of the Permanent Committee, the supreme body of the Chinese government, including the next head of state, Xi Jinping, and the next premier, Li Keqiang.

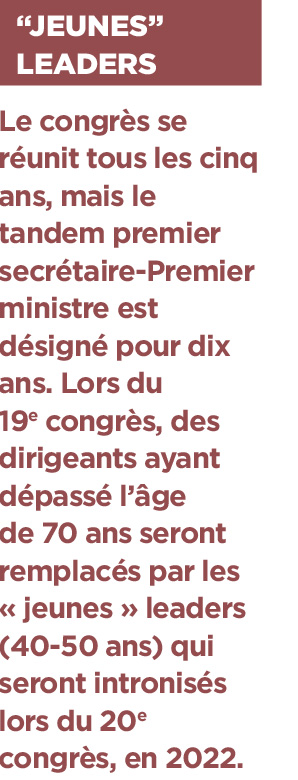

Fifth- and sixth-generation leaders

The Congress meets every five years, but the duo of first party secretary [head of state] and premier is designated for a ten-year period. The 18th Congress will designate leaders of the « fifth generation » since Mao. During the next congress — the 19th — the directors who have passed the age of 70 will be replaced by younger leaders of the « sixth generation, » in their forties and fifties, who will in turn be enthroned in the 20th party congress in 2022.

***

The urgent issues that await Xi Jinping

Abroad: a sea of troubles

Maybe it is a result of the silent struggles between different factions as the 18th congress approaches, but since this spring, sparks have been flying between China and its neighbors around the East and South China Sea: Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan and Japan.

Beijing asserts sovereignty over all the islands and 80 % of the waters. Recently, violent nationalist demonstrations broke out over the issue of the uninhabited islands called Senkaku in Japanese, Diaoyu in Chinese, which are currently administered by Japan. There is a risk that the crisis could worsen, as Chinese ships try to enter Japanese territorial waters. At the same time, the conflict over the Paracel and Spratly archipelagoes in the South China Sea has continued to fester.

The overall increase in tension could mean that Beijing, or rather its most extreme nationalists, could slip into the « classic » madness of countries that suddenly become world powers and choose to deal with their neighbors by force.

However, China owes its economic rise to its integration into the global market, and to the billions brought in by commerce and foreign investment. The deterioration of the political climate can only hurt its economy, which can still not stand alone. According to observers, Xi Jinping is well placed to defuse this crisis. Having lived through the disasters of the Cultural Revolution in his youth, he has a horror of orchestrated demonstrations of mass passion. With his experience governing provinces that receive foreign investment, he is aware of their value and fragility. Above all, his close relationship with the military means that the troops will listen to him. It remains to be seen if the neo-Maoist fringe, furious at the dismissal of their champion, « princeling » Bo Xilai, will try to destabilize him.

Domestic: A hope for Tibet?

Intellectuals, journalists, artists and Internet users are not the only ones hoping for great things from the son of Xi Zhongxun. A less visible group, the “pro-reform princelings, » who are ideologically opposed both to the « neo-Maoist princelings » and the « money princelings, » are also awaiting the more and more urgent political reforms, which have been on hold since Tiananmen in 1989.

According to Beijing gossip, Xi recently met Hu Deping, the pro-reform leader, to discuss reform priorities. The two men know each other well, for their fathers, steadfast political allies, shared the same disgrace. Hu Deping is the son of Hu Yaobang, first party secretary during the 1980s, the most reformist and popular leader China has had to date. His dismissal in 1987 for « softness » toward student demonstrators led to the purge of Xi Zhongxun, who had been the only high official to protest the dismissal. In 1989, it was the death of Hu Yaobang that set off the spring movement of the students, which ended in a massacre.

The two old hands, Hu Yaobang and Xi Zhongxun, had another point in common, a very moderate position on Tibet. The elder Xi was the political commissar in the army that invaded Tibet. He had tried to lessen the shock for the Tibetans. When Mao gave him the job of managing relations with the great lamas, he became friends with the young Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama. Zhongxun even managed to preserve, all the way through the turbulent time of the Cultural Revolution, the gold watch that the Dalai Lama gave him before fleeing to India.

Since the revelation of these facts by WikiLeaks, along with other details, such as the interest Xi Jinping is said to show in Buddhism, Tibetans in exile at Dharamsala have begun to hope for a renewal of negotiations, which have been blocked for years. Such a gesture would perhaps put a stop to the dramatic wave of suicides by immolation, which has been casting a shadow over Tibetan affairs. Further, it might allow a peaceful resolution of 50 years of conflict.